Sahil Jayaram, Diana Abagyan, Tiansheng Sun

Project code repository, on GitHubAbstract

We present a novel approach to the task of multilingual morphological inflection that utilizes lexicostatistical information, focusing on the Oto-Manguean language family. Unlike the state-of-the-art approach on which ours is based, we forgo transfer learning, instead relying solely on data for the Oto-Manguean languages of interest. Consequently, our model falls notably short of the state of the art in overall accuracy. However, our results demonstrate that initializing language embeddings according to interlingual Levenshtein distances rather than at random produces results that are more balanced across languages, as well as higher overall.

Introduction

Morphological inflection is a common linguistic phenomenon in synthetic languages around the world. It is a word formation process in which a word is modified to reflect grammatical information. Morphological inflection systems have multiple important applications; for example, in machine translation, it is desirable for the translated text to contain correct inflected forms. Therefore, in recent years, there have been efforts to build automatic morphological inflection systems.

Although results for the task were higher than anticipated, participants acknowledge the fact that their models drastically underperformed for low-resource languages with complex inflection system, such as the Oto-Manguean language family [1]. Due largely to its large inventory of tones, which are also used extensively for inflection, Oto-Manguean languages have some of the most complex inflection systems in the world. However, there are morphological and grammatical similarities between the Oto-Manguean languages. Information regarding these similarities may be useful to predictive models.

Background

The Oto-Manguean Language Family

Oto-Manguean is a large and diverse language family indigenous to Mesoamerica but now found only in Mexico. For some languages in the family, decline continues, as their status is moribund or highly endangered. However, some branches, such as the Zapotecan and Mixtecan, enjoy lively communities. According to a 2005 census, there are 1,769,971 speakers of Oto-Manguean languages, of which 218,679 are monolingual. A large percentage of Oto-Manguean speakers, those of Zapotecan and Mixtecan languages, now live in Oaxaca, a state in Southern Mexico. Other speakers speak Otomi and Mazahua languages in central Mexican state of Mexico and Hidalgo. It is critical to incorporate these languages into the digital sphere, both to ensure equitable access and to promote language vitality.

Oto-Manguean languages have many interesting features, which complicate morphological analysis, but which may be leveraged for an automatic inflection system. All languages in the family are tonal, ranging in number of tones from two to more than ten, which bears morphosyntactic significance. The family’s inflectional morphology is considered to be among the richest in the world, consisting of multiple layering classes. Inflection occurs in the stem, affixes, or tonal changes, and these may all be present in one word [2]. Many Oto-Manguean languages, such as Mazatec, also have systems of whistled speech, which whistles out tone combinations of words. Moreover, the internal diversity of Oto-Manguean poses difficulties in developing a versatile tool.

At present, there is a stark lack of language technology for Oto-Manguean languages, even compared to other groups of indigenous American languages. Despite the number of active speakers, no Oto-Manguean languages have a Wikipedia page or any input methods on Windows or Mac. Compared to 16 online paper resources for the Uto-Aztecan languages, 15 for Quechuan, and 8 for Algic, only three online papers were published for Oto-Manguean resources as of 2018 [3]. The main computational resource for Oto-Manguean languages is the Oto-Manguean Inflectional Class Database [2], which includes over 13,000 entries in 20 Oto-Manguean languages, nine of which are used as inflection data in SIGMORPHON 2020 Task 0. There are also some efforts in machine translation; for example, the SimplesoftMX project translates Spanish into Zapotec, a major Oto-Manguean language spoken in Oaxaca. However, digital resources for Oto-Manguean languages are still very scarce, and unfortunately, many Oto-Manguean languages are considered “dead” in the context of digital presence and resources [4].

Related Work

Morphological inflection helps to alleviate data sparsity issues for low resource languages with rich morphology. For example, in machine translation, a morphological inflection system indicates where inflected forms of a word may occur infrequently or not at all in the corpus. The appropriate stem is inflected according to the morphological paradigm in the final translation. It has been shown that a morphological grammar, whether handcrafted or learned, significantly improves translation from English to a morphologically rich target language [5]. Morphological inflection models also have the potential to greatly assist predictive text keyboards and speech recognition, as well as educational tools [6]. The Inuktitut Morphological Analyzer aids students with highly agglutinating words. Educational tools are important for language vitality, as people are encouraged to learn and maintain use of the language.

Multiple organizations and projects focus on building multilingual morphological tools for under-resourced languages. One such organization is SIGMORPHON (Special Interest Group on Computational Morphology and Phonology). SIGMORPHON provides a forum for news of recent research developments in computational morphology and phonology. It also organizes shared tasks in which participants can provide solutions to important morphological problems.

In the SIGMORPHON 2020 Shared Task 0, participants were asked to design a model that generates morphological inflection for all languages. Development languages from 5 language families, including ten Oto-Manguean languages, was used for training and development. The participants then fine-tuned their model on a list of “surprise languages,” half of which were genetically related to the development languages, during the generalization phase. Finally, the participants’ models were evaluated on all previous languages. For Oto-Manguean languages, the performance was relatively poor, with a mean accuracy across systems slightly lower than average at 78.5%, and a variance that was high in relation to other language groups, with language-level accuracy ranging from 18.7% to 99.1% [1].

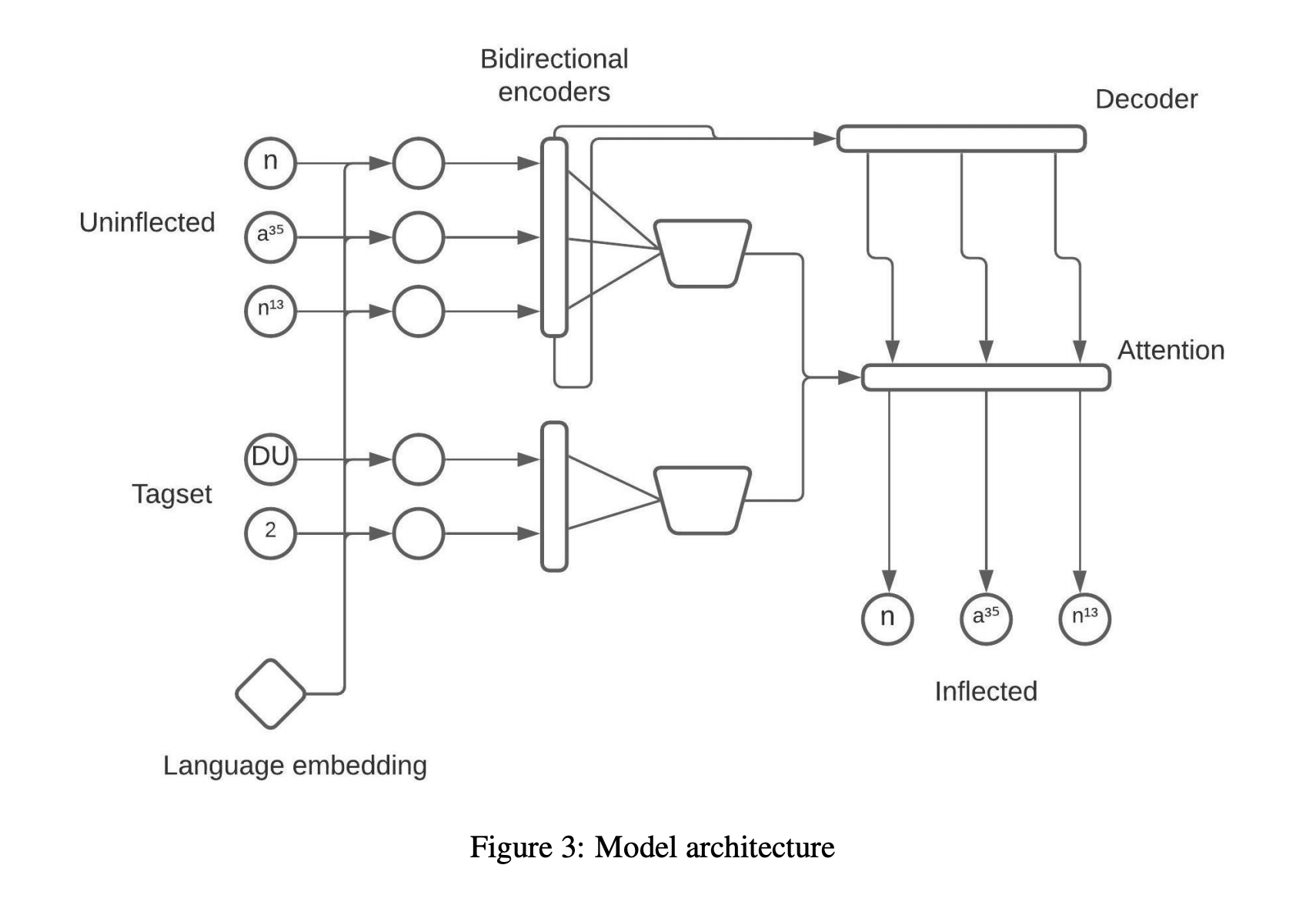

The system that achieved the highest accuracy across all languages was deepspin-02-1 [1]. deepspin-02-1 consists of a feedforward language encoder, two bidirectional LSTM encoders, and a unidirectional LSTM decoder (which incorporates a gated attention mechanism). For each input, one encoder encodes the lemma character sequence while the other encodes the set of inflectional tags. Then, the decoder generates the output character sequence [7]. The system reaches 83.45% accuracy overall for the Oto-Manguean language family.

Lexicostatistics

Lexicostatistics is a subfield of corpus-based linguistic methods concerned with determining the relationship between languages. Classical methods depend on cognate lists, or a Swadesh list. The Swadesh list is named for linguist Morris Swadesh, and is a list of essential concepts to language. The Swadesh list has been used in lexicostatistics, phylogenetics, and glottochronology since the first iteration in 1950 [8]. We do not have access to either a Swadesh list or cognate list for our languages, which complicates our analysis.

In our project, we rely on the concept of “linguistic distance” to initialize our embeddings. Linguistic distance is a measure of how similar two languages are to each other. Linguistic distance is warily regarded in linguistic literature, as there are many factors that may differ between two languages, such as syntax, phonetics, morphology, and so on. Reducing all of these complex inter-playing characteristics into a single distance score is difficult, if not impossible. Sophisticated methods use standard NLP techniques, such as computing a score based on the perplexity of an n-gram language model trained on one language on the test text of the other language [9], or by comparing word embedding distance [10]. However, we do not have access to a document-based corpus in order to train an n-gram language model, nor pre-trained word embeddings. Instead, we compute a measure of linguistic distance based on normalized Levenshtein distance, described in this section.

Our Mission

With technologies such as translation systems, spell checkers, language-specific keyboards, and dictionary apps, it is possible for digitally disadvantaged languages to “digitally ascend,” empowering speakers to participate in global online society using their mother tongues [4] [11]. This is particularly important for the 1.8 million Oto-Manguean speakers, 12% of whom are monolingual; the development of language technologies for Oto-Manguean could choke back systematic forces that exhort linguistic assimilation [2] [12]. Such forced linguistic assimilation has been known to cause irreparable damage to the groups affected [13].

Bird criticizes technologists who frame computational tasks for low-resource languages as “zero-resource scenarios,” ignoring the relevant knowledge of linguists and native speakers [12]. We believe that in the interest of language justice, solutions to the problem of automatic morphological inflection should be tailored to the language of interest, sharing cross-lingual information when necessary. For this reason, we adapt the deepspin-02-1 system introduced by Peters and Martins [7] to a much narrower domain–the Oto-Manguean language family–initializing language embeddings using prior knowledge of language similarity rather than doing so at random.

Methods

Data

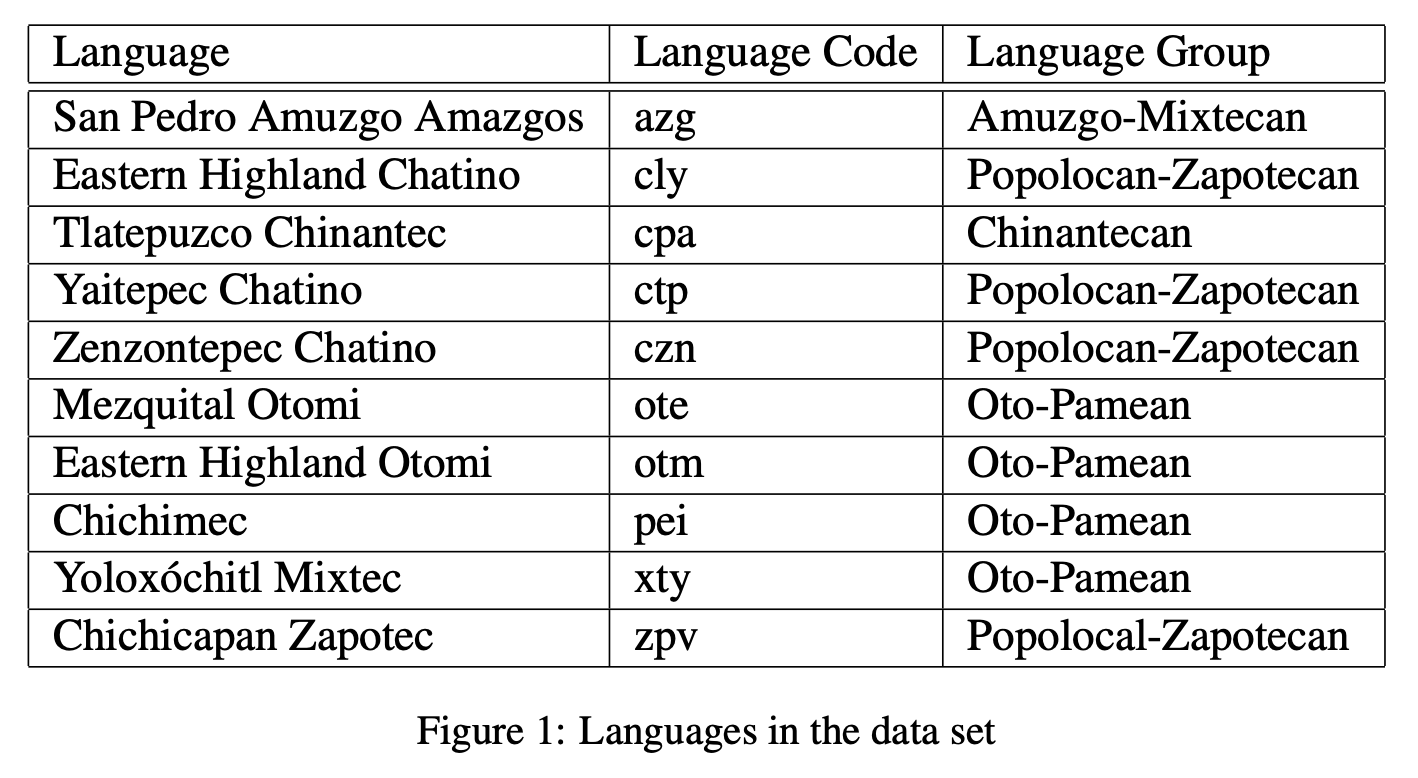

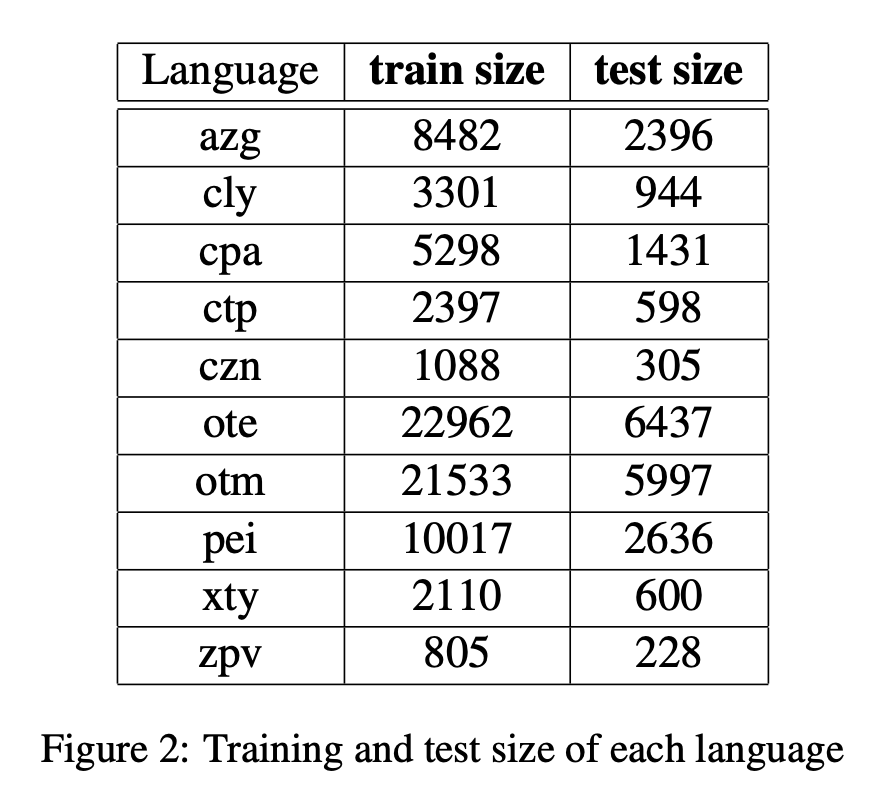

We obtain our data directly from the SIGMORPHON 2020 Shared Task 0 repository [1]. It contains 10 Oto-Manguean languages from a wide range of branches (Figure 1). Thus, our data is representative of most of the language family. The train set size for each language ranges from 805 (Chichicapan Zapotec) to 22962 (Mezquital Otomi), with an average size of 7799.3 (Figure 2).

The task dataset comes from two resources. The data source for 9 of the languages comes from the Oto-Manguean inflectional class database [14]. The data for the remaining language, Eastern Highland Chatino, comes from a Chatino corpus released in 2020 [15].

Each line of the data files is organized as follows:

lemma target form tags

where lemma is the original word, target_form is the inflected form, and tags is a list of (typically 4 to 5) rules that define the inflection, separated by semicolons.

The task is to convert the lemma to the target form based on the tags. For the purposes of our model, we represent words as sequences of characters, and tag sets as sequences of tags. Typically, one letter of a word is a character. However, tone superscripts are considered together with the preceding alphabet as one character. Each tag and character is assigned an index. In total, there are 30 tags and 414 different characters. The maximum character length of a word is 27. The words and tags are passed to the model as sequences of one-hot vectors.

Model

The general structure of our model is similar to that of Peters and Martins [7] (Figure 3). Our model differs from that of Peters and Martins in two ways. First, because the cardinality of our language set is 10 rather than 90, we use a language embedding size of 5 rather than 20. Second, in order to compensate for the scarceness and lower linguistic variance of our training data, we reduce the parametric complexity of the decoder’s attention mechanism by replacing gated two-headed attention with vanilla single-headed attention.

Linguistic Distance

We experiment with “smart” initialization methods for the language embeddings, informed by lexicostatistics. We use normalized Levenshtein distance as our linguistic distance measure, as defined by Petroni and Serva [16]. Levenshtein distance between two words is defined as the minimum number of insertions, substitutions, or deletions of a single character needed to transform one word into the other. The modification is normalized by the length of the longer word. Thus, for 2 words $wa$ and $wb$, normalized Levenshein distance $D_n$ is defined as:

$$Dn(wa, wb) = \frac{D(wa, wb)}{max(|wa|, |w_b|)}$$

Linguistic distance between two languages, $a$ and $b$, is defined as the average of normalized Levenshtein distance between all pairs of words from language $a$ and language $b$ that share the same definition. However, for one of our languages, Eastern Highland Chatino, the corpus does not contain definitions. Instead, for a given $wa$, we selected the $wb$ with the lowest Levenshtein distance to contribute to the average. Thus, we calculated linguistic distance $D_l$ between languages $a$ and $b$ according to the following formula:

$$Dl(a, b) = \frac{1}{|Wa|} \sum{wa \in Wa} \min{wb \in Wb}(Dn(wa, w_b))$$

For each language, a 5-dimensional embedding is randomly initialized. The language embeddings are found though optimization using the linguistic distances discussed in the previous paragraph, via stochastic gradient descent. Let P be the set of all unique, unordered language pairs, $va$ the current language embedding for language $a$, and $d{a,b}$ the calculated linguistic distance between languages $a$ and $b$. The loss function is defined as:

$$\sum{(a,b) \in P} \Big| \left|\left| va - vb\right|\right|{2}-d_{a,b} \Big|$$

Optimization is halted when the difference between loss values is lower than .005, averaging between 17-20 optimization rounds. This threshold was chosen manually by observing the plot of the loss function. Through this process, we achieve language embeddings that incorporate the linguistic distances between languages.

Experiments

We trained a total of 6 models (3 random seeds per initialization scheme). Our models were evaluated on the test set using a decoder beam size of 1, which we found to be optimal.

Findings

Results

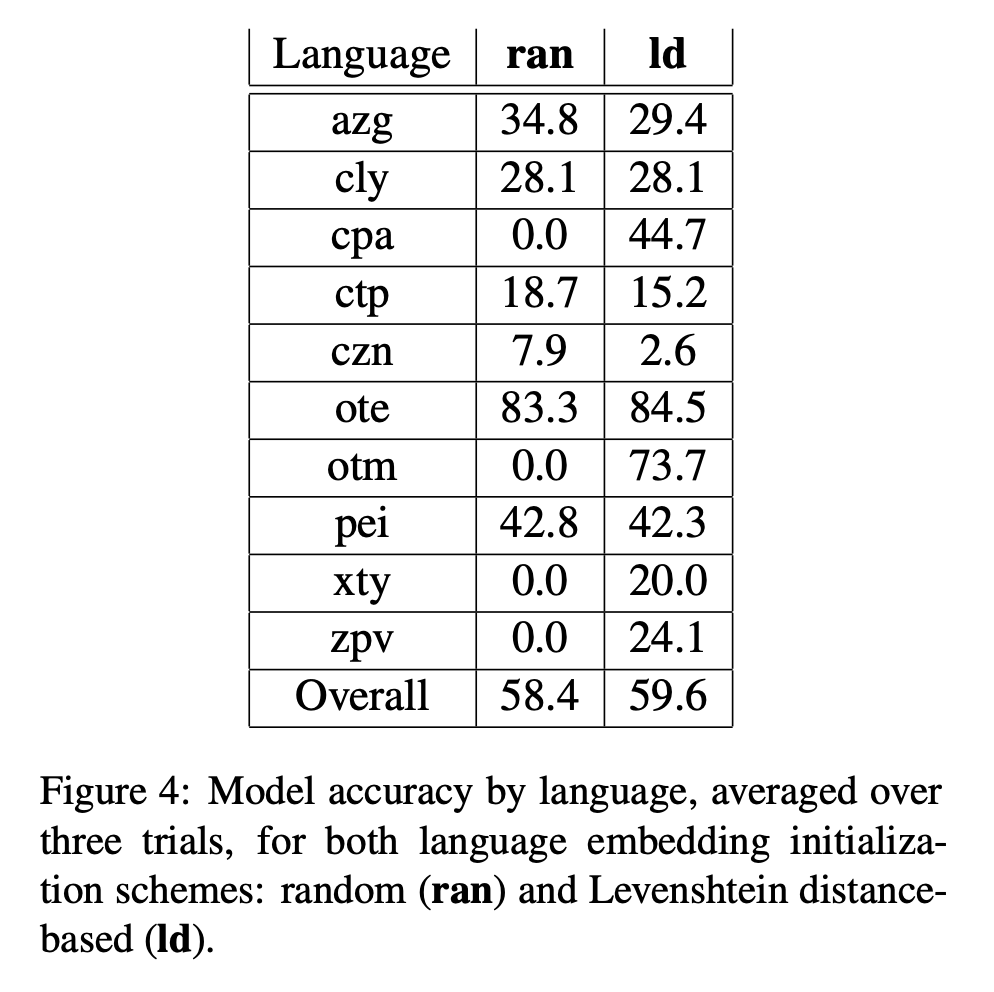

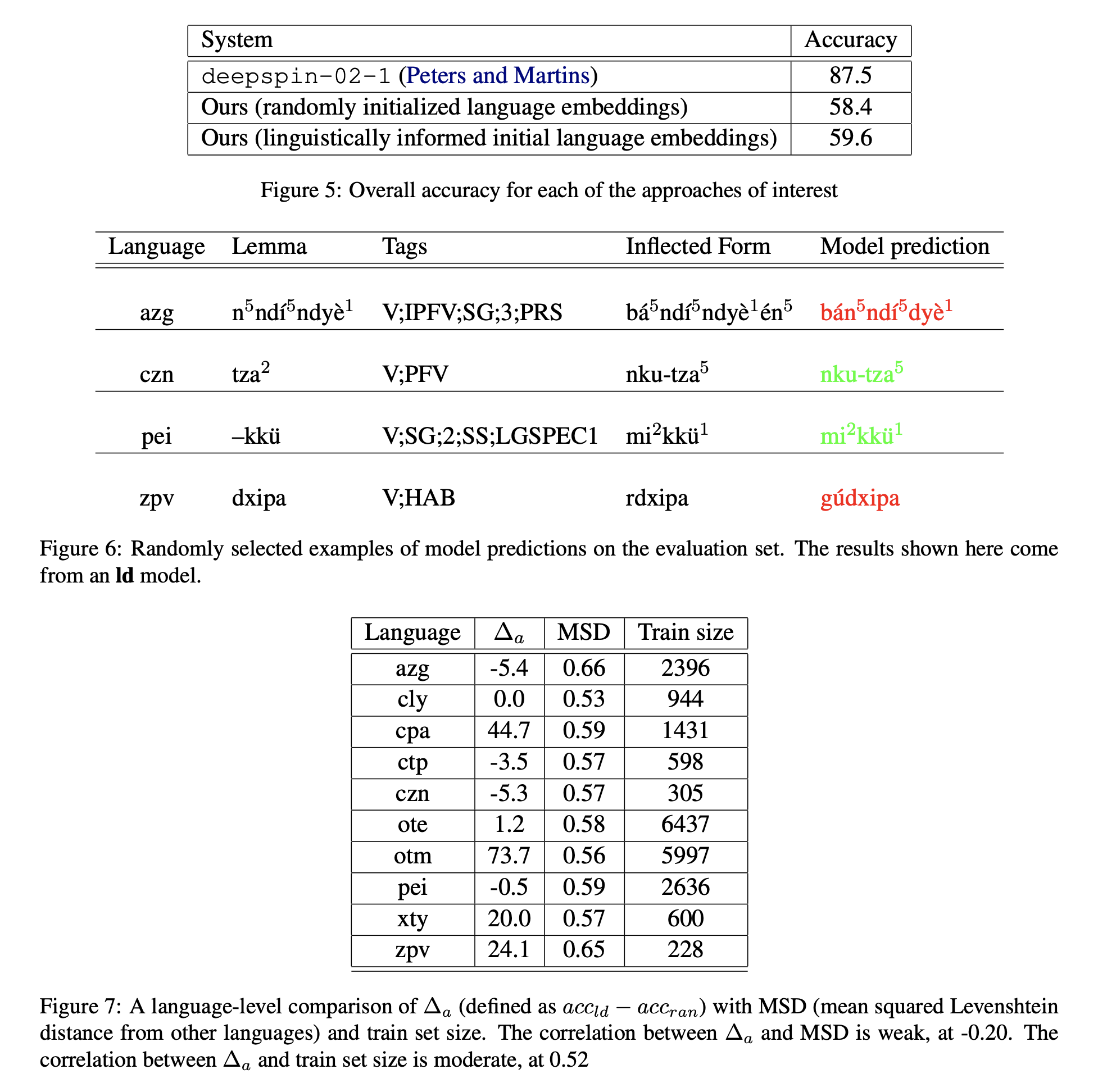

We present the averages of our results in Figure 4 and Figure 5. Our model achieves an overall accuracy of 58.4% using random initialization language embeddings, and 59.6% using Levenshtein distance, both of which are lower than the score achieved by Peter and Martins’ model (83.45%). We believe that the main reason for this discrepancy is that our system, unlike deepspin-02-1, did not utilize transfer learning, instead relying solely on data from the 10 languages on which it was evaluated. Figure 6 demonstrates our highest-performing model “in action.”

Error Analysis

Our results provide strong evidence that using Levenshtein distance information improves performance in a multilingual, low-resource scenario. With random initial language embeddings, several languages, such as Tlatepuzco Chinantec, Eastern Highland Otomi, Yoloxóchitl Mixtec, and Chichicapan Zapotec, received 0% accuracy. With Levenshtein distance, model performance on these languages improved significantly. Although we observed a decrease in accuracy for other languages, such as San Pedro Amuzgo Amazgos, Yaitepec Chatino and Zenzontepec Chatino, the models that accounted for Levenshtein distance achieved slightly higher overall accuracy and more balanced results across different languages.

We conducted an analysis to identify possible explanations for the aforementioned “balancing” effect. We found no strong correlation between the change in language-level accuracy from ran to ld ($\Delta_a$) and either train set size or mean squared Levenshtein distance. We present our analysis in Figure 7.

Conclusions

We have yet to determine the reason why using linguistically-motivated initial language embeddings, in lieu of randomly initialized language embeddings, produces the trade-off mentioned in here. However, we believe that the matter is deserving of further investigation.

Another key question worth exploring is whether our use of linguistic distance remains advantageous when applied in a transfer learning environment; if the benefits of lexicostatistical initialization persist in a higher-resource environment with more languages, e.g. the SIGMORPHON 2020 Shared Task 0 in its entirety, then our method may be of value for multilingual tasks in general.

Different measures of linguistic distance may also yield better results. Cognate or Swadesh lists, or any of the methods mentioned in here, would be useful to experiment with. Additionally, our Levenshtein distance measure may be improved by considering phonetics or historical linguistics. Difference in manner and place of articulation, as well as tonal differences, could be factored into the Levenshtein distance calculation. There may be work from historical linguistics in Oto-Manguean which could aid in our linguistic distance calculation. These did not come up in our literature review, but it would be a worthy avenue of consideration in the future.

It is also worth experimenting with alternative ways to utilize linguistic distance information. For instance, how does performance change when language embeddings are fixed during training, or when we introduce a loss term that encourages the model to learn lexicostatistic information by itself?

Last but not least, we believe it essential that future research in language technologies for Oto-Manguean languages utilize richer linguistic priors. To invoke Bird, it is irresponsible to ignore the wealth of information on these languages (grammatical rules, dictionaries, etc.) that linguistics and native speakers have collected and documented [12]. Thus, a continuation of this study should incorporate deterministic machinery that implements known properties of the languages of interest.

References

[1] Vylomova, et al. 2020. SIGMORPHON 2020 Shared Task 0: Typologically Diverse Morphological Inflection. In Proceedings of the 17th SIGMORPHON Workshop on Computational Research in Phonetics, Phonology, and Morphology, pages 1–39, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[2] Enrique L. Palancar and Jean Leo Leonard. Tone and Inflection: New Facts and New Perspectives. DeGruyter Mouton.

[3] Manuel Mager, Ximena Gutierrez-Vasques, Gerardo Sierra, and Ivan Meza. Challenges of Language Technologies for the Indigenous Languages of the Americas. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics.

[4] Andras Kornai. Digital language death. PLoS ONE, 8(10).

[5] Victor Chahuneau. 2013. Translating into Morphologically Rich Languages with Synthetic Phrases. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[6] Antonios Anastasopoulos and Graham Neubi. 2019. Pushing the Limits of Low-Resource Morphological Inflection. EMNLP.

[7] Ben Peters and Andre F.T. Martins. 2020. DeepSPIN at Sigmorphon 2020: One-size-fits-all Multilingual Models. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[8] Pablo Gamallo, Jose Ramom Pichel, and Inaki Alegria. 2020. Measuring Language Distance of Isolated European Languages. Information, 11(4).

[9] Pablo Gamallo, Jose Ramom Pichel, and Inaki Alegria. 2017. From language identification to language distance. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 484:152–162.

[10] Ehsaneddin Asgari and Mohammad R.K. Mofrad. 2016. Comparing fifty natural languages and twelve genetic languages using word embedding language divergence (WELD) as a quantitative measure of language distance. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Multilingual and Cross-lingual Methods in NLP, pages 65–74, San Diego, California. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[11] M. Benjamin. 2016. Digital language diversity: Seeking the Value Proposition. In Collaboration and Computing for Under-Resourced Languages: Towards an Alliance for Digital Language Diversity, page 52–58.

[12] S. Bird. Decolonising speech and language technology. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING), page 3504–3519.

[13] S. Romaine. The global extinction of languages and its consequences for cultural diversity. In Cultural and Linguistic Minorities in the Russian Federation and the European Union, page 31–46. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland.

[14] Timothy Feist and Enrique L. Palancar. Oto-Manguean Inflectional Class Database. University of Surrey.

[15] Hilaria Cruz, Antonios Anastasopoulos, and Gregory Stump. 2020. A Resource for Studying Chatino Verbal Morphology. In Proceedings of the 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, pages 2827–2831, Marseille, France. European Language Resources Association.

[16] Filippo Petroni and Maurizio Serva. 2010. Measures of lexical distance between languages. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 389(11):2280–2283.